Bioprinting Metrology: Tissue Structure Verification Standards

The precision demands of bioprinting metrology are escalating as 3D bioprinting transitions from research labs to clinical applications. Unlike traditional manufacturing, biological 3D printing measurement requires simultaneous assessment of structural integrity and biological viability, two factors that traditionally pull in opposite directions. As a metrology engineer accustomed to explicit tolerances in mechanical components, I've found that bioprinting presents unique challenges where environmental stability and measurement capability must be engineered across process, tool, and environment, not purchased off a shelf.

This article addresses the most pressing questions from manufacturing and quality professionals entering the bioprinting space. I'll apply methodical metrology principles to clarify how tissue engineers can build trustworthy measurement systems where traditional gauges often fail. When temperature fluctuations once caused a surface plate drift that scrapped a batch on Monday morning, the data convinced management to invest in environmental control. If you’re new to root-cause analysis for metrology failures, review our measurement error types guide to systematically separate instrument, method, and environment contributors. The same rigor applies here: bioprinting metrology requires understanding what you're measuring, how you're measuring it, and under what conditions, with assumptions and environment noted.

What makes tissue structure verification fundamentally different from conventional metrology?

In conventional dimensional metrology, we measure solid, stable materials with predictable properties. Biological constructs introduce multiple variables that challenge traditional measurement approaches:

- Dynamic material properties: Bioinks change state during and after printing (hydrogels crosslink, polymers set)

- Living components: Cells respond to environmental conditions during measurement

- Multi-scale requirements: Must verify macro-structure (millimeter-scale geometry) while ensuring micro-structure (pore size, cell distribution) meets specifications

Traditional coordinate measuring machines (CMMs) designed for metal parts can't account for the time-dependent deformation of hydrogels. A ±5μm tolerance stack that works for aerospace components becomes meaningless when the material itself may swell or shrink by 10% during measurement. This is where measurement capability must be engineered, not assumed from specification sheets.

"Shop by tolerance stack, environment, and workflow, or accept drift."

The NIST Workshop on Biofabrication Metrology confirmed this when 87% of participants identified environmental control as critical for reproducible measurements. Temperature swings affect both measurement equipment AND the biological material. Unlike metal parts that stabilize at room temperature, tissue constructs often require measurement at physiological temperatures (37°C), creating thermal drift challenges that demand explicit tolerance budgets.

How do we define meaningful tolerances for tissue constructs?

Tolerance analysis in bioprinting must consider both structural and biological requirements. A printed vascular network might require:

- Geometric tolerance: ±50μm for vessel diameter (structural requirement)

- Functional tolerance: 90% cell viability within 200μm of lumen wall (biological requirement)

These two tolerance requirements often conflict. Higher resolution imaging for structural verification might use techniques that damage cells. ASTM F3659 addresses this tension by requiring bioink characterization to include both rheological properties (for deposition accuracy) and cytotoxicity testing.

Consider a case study from a regenerative medicine facility:

| Requirement | Traditional Metrology Approach | Bioprinting Challenge |

|---|---|---|

| Dimensional accuracy | Micrometer measurement of final part | Construct changes dimensions during measurement as hydrogel absorbs media |

| Surface finish | Surface roughness gauge | Topography affects cell adhesion; requires correlation between optical measurements and biological response |

| Form tolerance | CMM verification | Living tissue settles under gravity during measurement |

This table demonstrates why tissue structure verification requires context-specific measurement protocols, not just off-the-shelf equipment. Your tolerance stack must include biological response thresholds, not just dimensional limits.

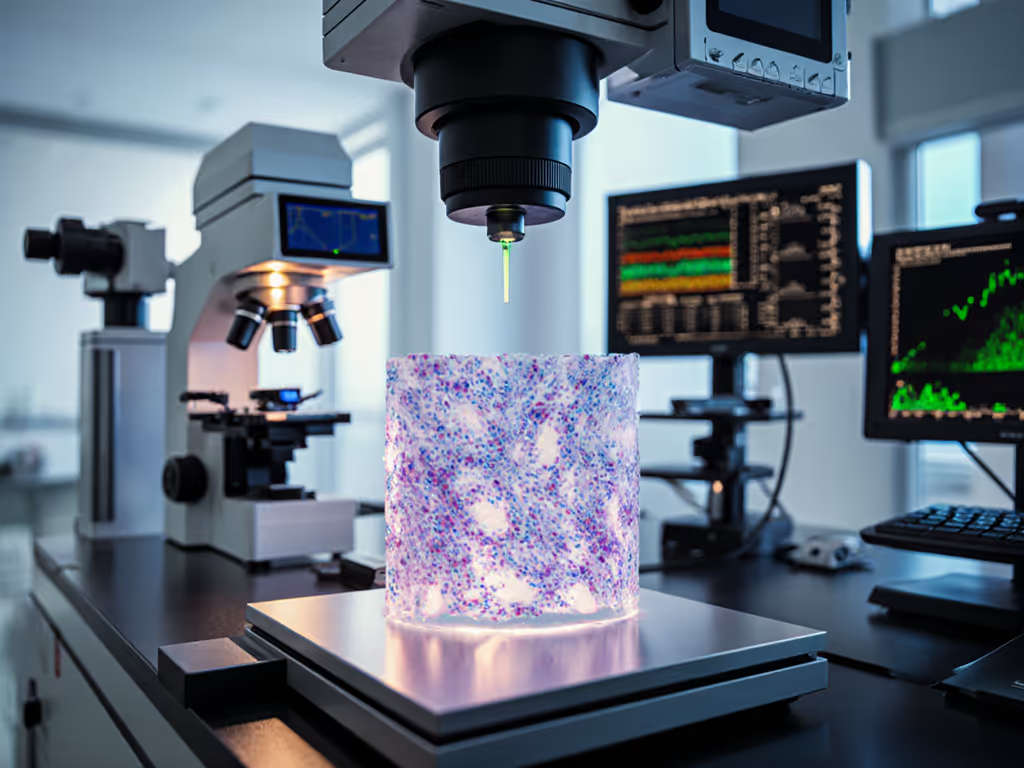

What are the most reliable techniques for non-destructive scaffold integrity measurement?

Traditional destructive testing won't work when you're measuring living constructs. From my experience correlating lab and shop data, the most promising approaches include:

-

Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT): Provides cross-sectional imaging without labels at 1-15μm resolution. Particularly valuable for scaffold integrity measurement as it can track construct changes over time. A 2023 study demonstrated OCT's ability to detect 20μm dimensional changes in hydrogel structures with 98% correlation to post-processing measurements.

-

Micro-CT with contrast agents: Delivers 3D structural data at 5-50μm resolution. Critical limitation: requires contrast agents that may affect cell viability, creating a trade-off between measurement accuracy and biological validity.

-

Structured light scanning: Effective for surface topology but limited to exterior features. Best paired with other techniques for complete tissue structure verification.

The key metric isn't resolution alone but measurement repeatability under physiological conditions. For a refresher on why repeatability and trueness are different, see accuracy vs precision with practical examples. When selecting equipment, engineers should demand uncertainty budgets that include environmental fluctuations, not just device specifications at 20°C. I've seen facilities waste six-figure investments because they didn't account for thermal drift in incubator environments.

How does environmental control impact bioprinting metrology accuracy?

During a summer heat wave, our surface plate thermal expansion caused a batch to be incorrectly rejected, a cautionary tale that applies directly to bioprinting environments. Temperature fluctuations of just 2°C can cause hydrogels to expand or contract by 3-5%, while also affecting optical calibration of imaging systems.

Consider these environmental impacts on bioprinting metrology:

- Temperature: Affects both measurement equipment (thermal expansion of stages/optics) AND biological material (hydrogel swelling, cell metabolism)

- Humidity: Critical for open imaging systems where evaporation alters construct dimensions

- Vibration: Disrupts high-resolution imaging and affects delicate cell constructs

- Light exposure: Can trigger unwanted crosslinking in photopolymerizable bioinks

A robust metrology system requires environmental uncertainty components added to the total budget. In one facility I audited, vibration from nearby equipment caused 15μm positional errors in high-magnification imaging, errors that disappeared when measurements moved to an isolated optical table.

What standards currently guide biological 3D printing measurement practices?

Several frameworks provide essential guidance, though the field remains in development:

- ASTM F3659: Standard Guide for Bioinks Used in Bioprinting establishes requirements for bioink characterization including viscosity, gel point, and cell viability, critical for bioink deposition accuracy verification

- ISO/ASTM 52900: While a general AM standard, it provides a foundation for process control documentation

- VDI 5708: German standard offering practical guidelines for bioprinting process validation

- ISO 10993 series: Essential for biocompatibility testing of all materials, including final constructs

These standards differ from traditional metrology frameworks by requiring measurement of biological responses alongside dimensional properties. To ground your quality system, start with measurement traceability fundamentals that link instrument calibration to national standards. The emerging NIST Biofabrication Consortium is developing reference materials for tissue constructs, addressing a critical gap identified in the 2024 NIST workshop where participants unanimously called for standardized testing and reference materials.

The most progressive facilities implement an integrated measurement system that tracks:

- Raw material specifications (with traceability to lot numbers)

- Process parameters (temperature, pressure, speed) with uncertainty budgets

- In-process verification points

- Final construct measurements with correlated biological response data

How should quality managers build uncertainty budgets for bioprinted medical products?

Conventional uncertainty budgets fail in bioprinting because they ignore biological variability. A comprehensive approach should include:

- Measurement system uncertainty: Traditional components (resolution, repeatability, calibration uncertainty)

- Biological response uncertainty: Natural cell-to-cell variation, metabolic state

- Environmental uncertainty: Temperature, humidity, and vibration effects during measurement

- Process-induced uncertainty: Variation from printing parameters affecting structural properties

For a critical vascular graft application requiring 200μm lumen diameter:

| Uncertainty Component | Value | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Measurement system | ±15μm | Calibrated OCT system at 37°C |

| Hydrogel swelling | ±25μm | Measured at 24h post-print in culture media |

| Cell layer thickness | ±30μm | Histology-confirmed variation |

| Total uncertainty | ±54μm | Combined using root-sum-square method |

This total uncertainty (±54μm) becomes the functional tolerance, even though the geometric specification might be ±20μm. Without this comprehensive approach, facilities risk producing structurally perfect but biologically non-functional constructs. I've reviewed multiple failed FDA submissions where companies focused solely on dimensional accuracy while ignoring biological response variation. For a regulated overview of life-critical measurement requirements, read our medical metrology audit guide.

For cell viability monitoring specifically, the measurement challenge is particularly acute. Live/dead assays show 15-20% variation between technicians even with identical protocols, a human-factor uncertainty component often overlooked in traditional metrology. Pairing automated imaging with standardized protocols reduces this to 8-10%, but never eliminates it entirely.

What's the path forward for bioprinting metrology standardization?

The field requires coordinated development across three areas:

- Reference materials: Standardized tissue mimics with known properties for instrument calibration

- Integrated measurement systems: Platforms combining structural and biological assessment without destructive steps

- Common data frameworks: Standardized reporting formats linking dimensional data to biological outcomes

Until comprehensive standards exist, bioprinting facilities should implement a tiered approach:

- Level 1: Document all measurement conditions with environmental parameters

- Level 2: Establish process-specific uncertainty budgets including biological variability

- Level 3: Correlate dimensional measurements with biological response data

Facilities implementing this approach have reduced validation failures by 60% according to recent industry surveys. The most successful organizations treat measurement capability as a system to be engineered, not a box to be checked during audits.

Final Considerations for Quality Professionals

As bioprinting transitions from research to regulated manufacturing, quality teams must evolve their metrology approach. Traditional tools designed for inert materials won't capture the dynamic nature of living constructs. The most reliable measurement systems emerge when engineers treat bioprinting metrology as a holistic capability, integrating environmental control, measurement technology, and biological validation into a single engineered system.

Remember that every measurement has its domain of validity. An optical scanner might provide beautiful structural data at room temperature, but that data becomes irrelevant if the construct behaves differently at 37°C. Always document your measurement limitations with explicit tolerances and uncertainty components, not just the results.

For those ready to deepen their understanding of bioprinting metrology, I recommend exploring the NIST Biofabrication Consortium's latest white papers on reference materials development and the ASTM F42.04 subcommittee's work on bioprinting standards. These resources provide practical frameworks for building measurement systems that balance structural precision with biological reality, ensuring your bioprinted products meet both dimensional and functional requirements.